NASA spacecraft's fiery finale will give us glimpse of Saturn's rings

The gap between Saturn and its innermost ring is unknown territory, potentially strewn with flying dust that could devastate anything in its path. Now the first spacecraft is about to venture into that unexplored realm.

Seasoned NASA spaceship Cassini will dive into the gap later this month for an unparalleled research campaign nicknamed the Grand Finale. The name is not hyperbole: Once it has fulfilled its mission, Cassini will plunge into the heart of Saturn, ending 13 years of unprecedented scientific discoveries.

“We are going in and we are not coming out,” Cassini project manager Earl Maize of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory said at a briefing Tuesday. “It’s a one-way trip … a spectacular ending, going out in a blaze of glory.”

After it punctures Saturn’s cloud tops, the spacecraft will survive perhaps three minutes until it succumbs to the intense heat and pressure. It will disintegrate, and its pieces will first melt and then vaporize, making Cassini “a part of the very planet it left Earth 20 years ago to explore,” Maize said. It took seven years for the spacecraft just to reach Saturn.

Even in its final minutes, the spacecraft will beam back data about the atmosphere’s composition. And the last few months of Cassini’s career promise to be among the most fruitful in a mission that has astounded and delighted scientists.

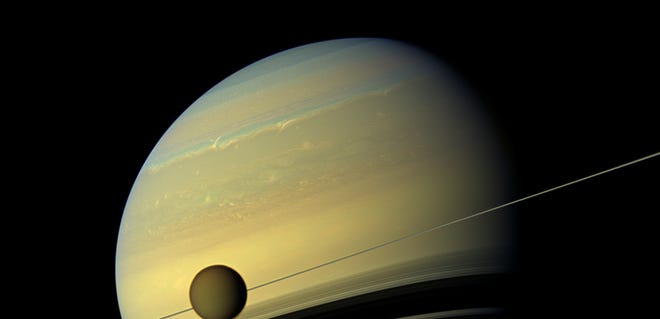

On April 22, the craft, which launched in 1997, will whip by Saturn’s biggest moon Titan, an encounter that will nudge Cassini onto a path so audacious that prominent planetary-science commentator Emily Lakdawalla once said it seemed “totally crazy.” Cassini will hop over Saturn’s rings, which form a gauzy collar of dust and ice around the giant planet, and begin threading the needle between Saturn’s atmosphere and the D ring, which begins only 1,200 miles from the planet itself.

Over the next five months, Cassini will orbit Saturn 22 times, whizzing along at some 76,000 mph. A hit from a single particle of dust could cripple one of its instruments. So for the first few orbits at least, the spacecraft will fly with its huge dish antenna forward, shielding most of the precious science equipment. If engineers are correct about the amount of dust, they’ll be able to turn the spacecraft so the instruments can collect more data.

Read more:

NASA's Cassini finds liquid-filled canyons on Saturn's moon Titan

Saturn's hexagon-shaped storm stuns in new close-up images

NASA’s Cassini captures jaw-dropping photos of Saturn’s rings

The resulting information “might be the best of the mission,” said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker, also of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Cassini will record data about the rings’ mass, which will help settle the debate about how the rings formed. It will get a close look at the giant hexagonal jet stream at the planet’s north pole, as big across as two Earths, Spilker said.

The spacecraft will skim so close to Saturn that it will pick up clues about the planet that could not be gathered any other way. “Getting this close to the rings and the planet – that’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience for a scientist like me,” Spilker said.

After 20 years in space, Cassini is burning through the last of the fuel needed by its steering thrusters. NASA does not want an out-of-control spaceship blundering into Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Titan, which could either host life or once have done so. The safest course is to send the ship to its demise.

“It’s really going to be hard to say goodbye … to this plucky, capable spacecraft that has returned all this great science,” Spilker said. “On that final day, it will be a very hard time.”