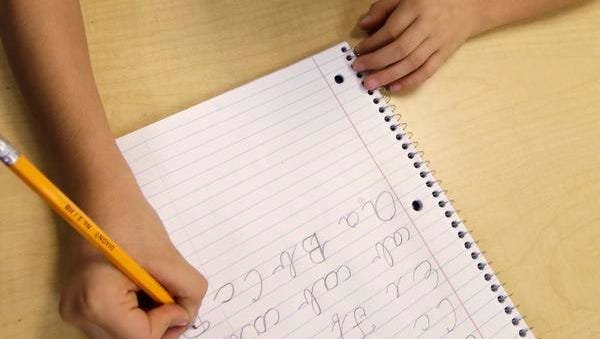

Bipartisan bill would bring cursive back to schools

With the increasing prominence of cellphones and computers, some Delaware lawmakers are concerned that cursive writing is becoming a lost art.

So, they are crossing party lines this month to sponsor a bill with one goal: to bring cursive writing back to public schools.

"Under current educational standards, students are no longer required to be taught cursive writing and many schools have abandoned teaching cursive writing to students," says the bill, sponsored by Rep. Andria Bennett, D-Dover. The proposal also has several Republican sponsors and co-sponsors.

"As cursive writing is still an imperative skill in many professions, this bill makes teaching cursive writing a requirement for all public schools in Delaware."

Dory Zinkand, director of academic resources at Tall Oaks Classical School, believes cursive should be taught to students, but for different reasons. The benefits of cursive go behind writing, she said, and can impact a child's growth.

It has been proven that cursive can impact cognitive development, partly because it involves both fine motor skills and visual and tactile processing. Writing in cursive requires both sides of the brain, scientists say, and promotes language and memory functions.

MORE: Mike Matthews wins election for DSEA president

MORE: DelTech, Widener open pathway to legal studies degree

That's why Tall Oaks teaches all students cursive and includes it in its curriculum. Not only that, but the incidence of dyslexia in children who start learning cursive in kindergarten is actually lower than it is for kids who don't, Zinkand said.

Because cursive — unlike print writing — requires you to keep your pencil to the paper, there's less room for distractions when writing. Holding a pencil and practicing cursive activates the parts of the brain that lead to increased language fluency and can aid in letter recognition, studies have shown. It can also help kids write physically faster.

"Cursive is actually used as a therapy for kids who are dyslexic," said Zinkand, who has a background in education therapy. "I think if public schools really drop cursive, you'll see an increase in dyslexia and a decrease in reading comprehension."

Out of style?

Despite evidence of its benefits, cursive writing is not included in Common Core, a set of U.S. education standards adopted by more than 40 states, and an increasing number of states have dropped it from their curriculum in favor of what is explicitly required.

A 2013 study of elementary teachers from across the U.S. found that more than 40 percent have stopped teaching cursive, while among students who went to elementary school in the 1990s, only 15 percent used cursive writing on their SAT exams.

On Facebook this week, some DelawareOnline readers said they didn't think cursive was necessary anymore.

"I'm not sure I see the value," Erika Norbut Collier said. "It's something I learned in school, but rarely use; I type everything. My 8-year-old is not being taught it in school, and I suspect he will never learn to write that way. He also types nearly everything. He does however have to read it at times. His teachers write notes that way. His grandparents send him letters and postcards. If he's having trouble making something out, I help him. I feel taking time to teach computer skills is more important that taking time to learn to write in cursive."

Others pointed out that several historical documents — including the Constitution — are written in cursive and said students should be able to read them in their original forms. Some thought cursive is important even if you just use it to sign your name; printing it just isn't the same.

Still others mourned the loss of writing style and equated it to the loss of a shared history.

"I handwrote all of my girls' favorite recipes, put them in a cookbook and gave it to them as a gift," one reader said on Facebook. "Imagine how upset I was to find out my granddaughters couldn't read a word."

"I write notes on my favorite recipes — when I'm gone, how will they read them?"

Contact Jessica Bies at (302) 324-2881 or jbies@delawareonline.com. Follow her on Twitter @jessicajbies.